Thank you for reading this week’s Jason Ward Creative Substack piece. It was inspired by an office building that made me consider the importance of architecture in our emotions, our stories and the characters that we create. I appreciate you spending your time with me and would love you to subscribe to the Jason Ward Creative Substack where you will find around 70 articles, podcasts, reviews and playlists. Subscription is currently free of charge and I look forward to welcoming you in. Enjoy the piece

Elvis Costello famously said “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture” to describe the futility of using words to describe something as emotional and all encompassing as music. The quote is well known but only makes sense if you think that buildings cannot affect us emotionally.

But buildings do affect our emotions and can influence us as much as music, dance or prose. Think about the words used on TV house makeover shows: creating cosy rooms or airy spaces and areas for entertaining. ‘Cosy’ evokes closeness and safety, whereas ‘airy’ is about feeling you have space to express yourself and ‘entertaining’ implies happiness, togetherness and sharing.

The external form of a building influences emotions as much as the inside. The shape can be dominating and designed to frighten like castles or corporate head office buildings which are big, solid, shiny and secure.

Brutalist architecture evokes anger and rage as it diminishes human scale - the feeling might be negative but it is still an emotional response. Every time I arrive into Southampton and see the hideous blocks of Wyndham, Court built near the railway station I feel anger at their ugliness and a sense of powerlessness, futility even, that the building’s design was prioritised over human need. The generation of planners and architects who imposed this style on many British cities have much to answer and atone for.

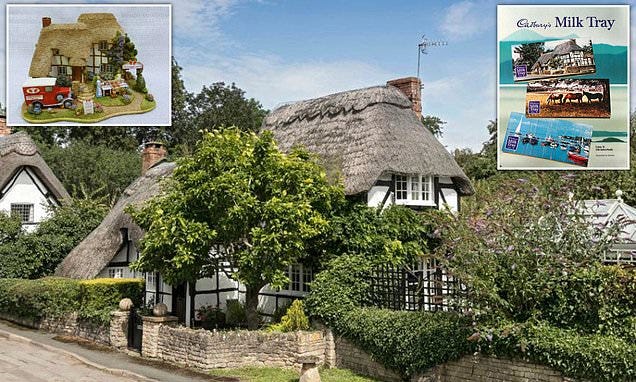

Conversely, some buildings feel like they are designed to embrace us or maybe we are conditioned to associate certain architectural forms with a feeling of being ‘home’. In the UK many of us are programmed to call a certain type of small house a ‘chocolate box cottage’. This refers to a particular type of house that would have once appeared in picturesque scenes that decorated Cadbury’s boxes of chocolates. This tradition started in the 1950s and 1960s when Cadbury’s chocolates would have been bought as a treat for working class families so the cute little cottages become associated with the pleasure of eating chocolate and the joy of a special occasion. Both are strong emotions that condition people to feel that a particular style of building is linked to happiness.

There is a building I pass on Christchurch Road when I go into Bournemouth city centre. It is a red brick built office block with a glorious scalloped and contrasted sandstone coloured border around its immense front door. It is a proud and hopeful building known as Telephone House that stands out for its colour, form and attitude. Either side of Telephone House stand two nasty 70s office blocks, designed by architects with a strong sense of aesthetic sadism and a desire to absorb and shut down any sense of joy or hope that should be felt entering the centre of a Victorian seaside town. Both 70s buildings look damaged and damaging while in the middle Telephone House stands proud, built from bricks that were laid one at a time by hand.

What gives Telephone House more presence is the feeling that it is reaching out across the road to another time and to an art deco style building called Beacon House which is the first in a run of entirely brick buildings that lead to the glorious Victorian Landsowne college building with its clocktower, dome and columns.

These are buildings that feel like they would tell a positive story - a human story. The grim grey 70s blocks are the opposite of human - their stories would be of corporations, or of Government departments and would all feature large entities that are far from human in scale.

Although Telephone House is 5 storeys high (and has served as offices for JP Morgan) there is something in its material and form that makes us think of it in more human terms - houses are built of brick, cottages are made of brick, bricklayers are skilled tradespeople who work with bricks. The building’s Georgian symmetry, its colour and texture trick us into easily imagining Telephone House as an actual house - a home, a place where people ( humans) live. A very big house but a house nonetheless!

The type of stories that buildings can tell is important to us creatively. We need to consider and reflect on the emotions that buildings evoke because that will lead our stories. We expect James Bond to report to his boss in a dominating building that is filled with high tech gadgetry but we also expect him to have hidden or secret offices tucked away in the back of carpet shops in Istanbul or in disused Tube stations in London.

In another classic British spy story John Le Carre painted MI6 HQ at the Circus as a drab, tedious and visually uninspiring building. This fitted the character of the work that his spy George Smiley was carrying out which was drab, tedious and visually uninspiring. Much of Smiley’s work was internalised, involving thought, planning and strategising rather than the fighting, flying and fucking that Bond was known for.

Bond would never spend 5 days hidden in a cold West Berlin attic waiting for a subtle sign from across the wall that a defector was ready to cross. Whereas Smiley would never drive a Lotus Esprit that turned into a submarine or report into a shiny Thames side, hi tech HQ.

There are a whole host of architecture references in musical theatre as well. In Sondheim’s ‘Country House’ we see a couple who have grown apart and are looking for the ‘thing’ that will pull them together. The idea of a Country House evokes joy and maybe even cosiness and will surely solve their marital problems. Sondheim has a thing about houses in the country because he also sends all his characters to one in A Little Night Music!

In Rent the characters’ choice of place to live and style of life is totally reflective of them as people and is what drives the plot. The show shares a similar theme with In The Heights that also talks about how buildings can embrace and strengthen communities and warns us about how changing buildings’ can be destructive.

Perhaps the most beautiful architectural moment in musicals is from Little Shop of Horrors. At the top of the show we hear about the downbeat neighbourhood of Skid Row and how its residents want to escape it. But where do they want to go? Audrey tells us about the downtrodden city dwellers’ aspirations in the classic ‘Somewhere That’s Green’. During the song she explains the architectural and interior decor features of the house of her dreams. It is this building that signifies happiness for her with each of its features another step on the yellow brick road to a fulfilled and joyful life - and isn’t that what we all want?

A matchbox of our own

A fence of real chain link,

A grill out on the patio

Disposal in the sink

A washer and a dryer and an ironing machine

In a tract house that we share

Somewhere that's green.

He rakes and trims the grass

He loves to mow and weed

I cook like Betty Crocker

And I look like Donna Reed

There's plastic on the furniture

To keep it neat and clean

In the Pine-Sol scented air

Somewhere that's green

Between our frozen dinner

And our bedtime, nine-fifteen

We snuggle watchin' Lucy

On our big, enormous twelve-inch screen

I'm his December Bride

He's Father, he Knows Best

Our kids play Howdy Doody

As the sun sets in the west

A picture out of Better Homes and Gardens magazine

Far from Skid Row

I dream we'll go

Somewhere that's green.

Alan Menken / Howard Elliott Ashman

Thank you for reading this article. To support more creative musings on the Jason Ward Creative Substack please click below for a free subscription.Many Thanks- Jason