Could AI Create Musical Theatre?

Discovering if the Machines really are Beautiful for the Art Form

Thank you for taking the time to read the Jason Ward Creative Substack. Every week I write articles about pop culture and creativity with interviews, reviews and reflections. It would be great to have you along to share the ride by becoming a subscriber. Subscription is currently FREE and includes access to over 70 articles and podcasts. I look forward to welcoming you in.

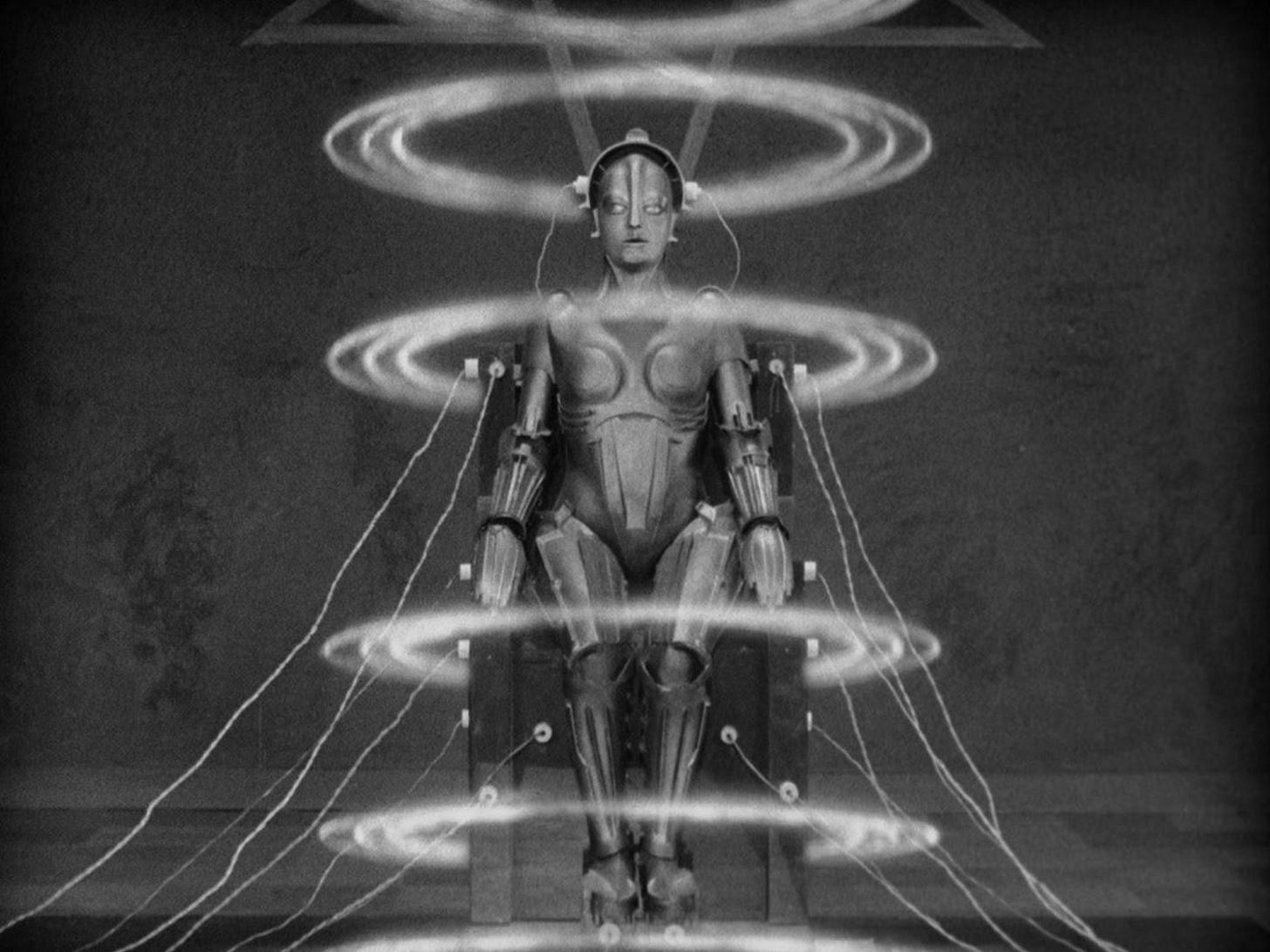

Humanity has been on a mission to dehumanise itself. Anything that is done by human hands and minds is fair game for inventors, programmers and businesses to replace with automation, machinery or apps. Like a budget airline that strips away all those supposedly unnecessary frills like free drinks, fair pay for staff and clean seats in search for the ultimate efficiency and profit lever we are stripping away so much of what it means to be human. And now we see machines moving into the creative industries replacing writers, and actors with machine code and efficiency - hence the current writers and actors strike in the USA.

Joan is Awful, a recent episode of Black Mirror, presented a not too distant time in which a streaming service produced AI generated TV featuring twisted versions of the lives of real people, and the ITV show Neighbour Wars has already used deepfake technology to show famous people in ordinary circumstances.

In the world of live theatre we might think ourselves immune from this relentless mechanisation. After all TV and film are digital creations and rely on technology to exist. Live theatre literally just needs a couple of kids in a barn and you got yourself a show!!

It would be dangerously complacent to imagine that theatre will not be affected by the use of AI. We have already seen accusations that some shows are literally ‘written by numbers’. Jukebox shows tend to attract this criticism because they can appear formulaic and, if we think about it, what that word actually means is that humans can learn a formula to create a hit show - and if humans can learn this formula then so can AI.

This is why we need, as an art form, to really focus on original writing for both straight and musical theatre. New and unexpected stories like Operation Mincemeat, Standing At The Sky’s Edge and A Strange Loop do not readily fit a standard formula - and who would ever have predicted the blockbuster success of SIX?!

If a machine were to analyse musical theatre right now would it look at movies as the best source material for new musicals? Or would it comb the back catalogues of rock and pop stars and sew together a loose narrative that would utilise several of their biggest hits and a couple of lesser known songs into a new musical? What the machine might do is what the theatre industry has been doing for years: look at what was a big hit most recently and try to follow that trend. All these choices preclude new ideas.

Broadway World asked AI app ChatGPT to come up with an outline for a new Broadway musical. The first attempt appeared to be derived from an existing Channel 4 documentary called Codebreakers, while the second was a tale of a group of teenage friends trying to save the world from an eco disaster. Neither of these concepts are that original which is probably down to the fact that AI can only draw from what already exists. It can only trawl through stories, plots and shows that have already been produced and use that information to propose its own version.

In a way this is also how human inspiration works - everything we experience inspires us in one way or another. However, the difference is that human creators can consciously reject everything that they know and everything that went before, whereas AI can only draw on the past and create a new version of what has already happened.

The unexpected, the nonsensical and the creatively dangerous are what drives art forward and are what we should be demanding of our theatre makers.

In the UK there is a house hunting programme called Escape to the Country. The show follows people who want to move away from towns and cities and live somewhere more rural. In every episode there is a section that I call ‘The Basket Weaving Bit’ in which the presenter meets someone local who is doing something traditional. It could be one of the last bookbinders in Wales or the only remaining wooden boat builder in Norfolk. What we see are trades and skills that were once ubiquitous but are now curiosities. We would never expect books to be bound by hand anymore but in the 19th Century nobody ever expected that a machine could carry out the bookbinder’s skilled work.

In 100 years time will the Escape to the Country Basket Weaving Bit feature the last know person in Wales still writing theatre - or still writing? Will humanity wonder why men and women worked themselves to the bone for years perfecting the structure and arc of their show? Will Producers look at AI as a great way to move creatives out of the way and make more money themselves? These are real questions that we need to discuss today because there is no reason why a machine cannot arrange and orchestrate music (and play all the instruments!), or choreograph dance numbers or design lighting and sound.

This dystopian view of the future is not intended to give anyone nightmares. Instead it is intended to make us all think about how we want to move forward. Theatre is not immune to technology and although it has done a fairly good job of making machinery its servant the next steps are uncertain. If we use AI to create theatre we will lose the chance to challenge and question or to surprise and delight. We will produce shows that deliver to expectations and are safe bets for punters and producers. We will leave theatres feeling a little moved, not really surprised and generally happy with our choice. The average will have won and theatre should never be average!